Early this fall, the FCC sent out a message inviting faculty to inform them of issues we would like them to take up this academic year (e-mail from Gary Engstrand, Sept. 13, 2010). FRPE members met and discussed this question, and we have now drafted a document articulating three main issues that we would like the FCC to address. We welcome suggestions as well as additional signatories to this document, which we shall presently send to the FCC in reply to their invitation. We also urge everyone to communicate their own concerns to the FCC, which you may do by writing to Gary Engstrand.

***

Issues that FRPE would like the FCC to address

Several members of Faculty for the Renewal of Public Education had the opportunity to meet with the Faculty Consultative Committee during its retreat at the start of the academic year, and to present issues with which we are concerned. The principal subjects we discussed at that meeting were these: 1) how to improve faculty governance, 2) the need for budgetary transparency and clarity; 3) restoring intellectual values to the work, self-conception, and public purpose of the University. We appreciate the work that the FCC and other Senate committees have already begun to undertake on such matters, in particular the issues of budgetary transparency and administrative costs. With the present communication we wish to reiterate our concerns about faculty governance, while making a couple of specific suggestions for improvement, and to present other issues that have become pressing.

1. Structure, powers, and mechanisms of faculty governance.

We urge the FCC to examine the current system and consider how it may be improved. At present the great majority of the faculty neither participate in university-wide governance nor see it as worth their while to do so. There are many reasons for this, starting with the disincentive that service in governance carries little reward (sometimes even negative rewards). Effective engagement is moreover inhibited by structural problems, such as the dissociation of the Senate as a (putatively) deliberative body from the committees that do most of the actual deliberation, and the incoherent process whereby the membership of those committees is constituted (with the exception of the FCC). But the overriding reason is encapsulated in the premise on which Mark Rotenberg based his opinion that the Minnesota Open Meeting Law does not apply to the FCC, to wit: that the statute applies only to the governing body or committees thereof “that have the capacity to transact public business on the part of the public body by making final policy decisions,” and that (only) “the Board of Regents is the governing body of the University of Minnesota” (minutes of the FCC meeting, Sept. 16, 2010).

Why then should any faculty member bother to participate in governance, when we actually possess no governing power?

While, as a matter of legal fact, Rotenberg’s statement of the case is correct, a clearer declaration of the vacuity of faculty governance is hardly imaginable. The FCC and all other faculty bodies have, according to the general counsel, no role in governing the University and no capacity to make policy decisions. (Any decisions the faculty do make – outside the limited areas explicitly marked out for unimpeded faculty control – may be neutralized, vacated, or simply ignored by the administration and the Board of Regents.) In the FCC’s discussion with President Bruininks (also summarized in the Sept. 16 minutes), Professor Chomsky aptly distinguished consultation from decision-making and acknowledged, in effect, that faculty have a role in the former but not the latter.

Consultation is not governance. If faculty are to have a governing role, rather than merely an expectation of being consulted, then, in accord with the statute cited by Rotenberg, perhaps it is necessary to begin by redefining the Senate and its committees as committees of the Board of Regents. It would further be necessary to restructure the allocation of powers between faculty and administration, so that, rather than the faculty carrying out the administration’s decisions, the faculty make policy and the administration carries out the faculty’s decisions. To facilitate such transformation, faculty should be represented on the Board of Regents, as students are; accordingly, we suggest that the FCC consider advocating for the inclusion of (a) faculty member(s) on the Board of Regents.

Short of radically transforming faculty “governance” so that it would merit the name, there are simple changes to elements of current procedure that could readily be put into effect and would immediately make small but tangible improvements. For instance:

a. Require that ayes, nays, and abstentions be called for and counted whenever the Senate votes on any matter that has policy implications. Under current practice, voice votes are often taken unless a Senator requests a counted vote, and abstentions are often not called. Thus the Senate can be said to have “decided” something when only an insignificant minority of Senators said “aye,” a smaller minority said “nay,” and the majority, perhaps feeling insufficiently informed by the insufficient deliberation to which they were privy, said nothing at all. Yet such “decisions” are accorded the same validity as if the whole body had participated in making them.

b. The president of the University is granted the role of presiding over Senate meetings. This is an anomaly given that, regardless of faculty status, in his capacity as president the president functions as an administrator (with a P&A appointment) rather than as a member of the faculty. Pending revision of the article that grants the president this role (University Senate constitution, Articles III.3, IV.3), the president should be bound by the same constraints that apply to all other Senators: he must await a turn to speak and be limited to three minutes. Inasmuch as the president (like other officers, faculty members, or invited guests) may sometimes be granted a longer period of time to present a certain issue, after having presented it he must be deemed to have had his turn, whereupon all other Senators wishing to speak have priority over him until the time for discussion is up.

We believe that making even these minor procedural changes would be a meaningful first step toward restoring credibility to the Senate as a governance body and redressing the gross imbalance of power between the administration and the faculty.

2. Rights of P&A employees.

We urge the FCC to lead an effort to enhance and support the rights of academic professional and administrative employees (P&A staff). This becomes urgent in consequence of the administration’s imposition, last June, of a policy arrogating to itself the right to change the terms of P&A employees’ contracts unilaterally, and to cut or defer their pay, at any time it wishes to declare financial stringency. It has now been made clear to P&A employees that they are actually supposed to work during the days they are “furloughed” – even though the University will be closed on those dates – and if they do not plan to work (off campus) through the furlough days, they must use personal vacation days as work days instead. This abuse of a category of employees lacking either the security of tenure or bargaining rights is repugnant. While some employees with P&A appointments are well-paid administrators, most are low-paid members of staff, without whose work the University simply could not function.

At a minimum, P&A employees should be accorded a binding vote on whether to take a pay cut, just as regular faculty are. While this employee group has its own representative body, the Council of Academic Professionals and Administrators, in the view of many P&A staff CAPA has proven utterly ineffective at protecting their interests. Under these circumstances it is incumbent on the regular faculty to advocate for our P&A colleagues’ right to fair treatment.

3. Inclusion of students in governance.

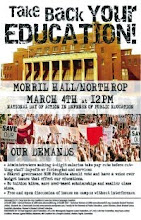

We urge the FCC to support a requirement that student representatives be included in the process of consultation and decision-making on all matters of policy that affect students, especially those policies that students participate in implementing. Members of the Minnesota Student Association have been advocating for such a requirement, citing a comparable Wisconsin statute as precedent. The token student representation on various task forces and committees (such as the so-called “blue-ribbon committees” charged with proposing ways to restructure colleges) is widely regarded as woefully inadequate. Students were excluded from consultation on the revised Conflict-of-Interest policy, although students will participate in its implementation. Recently, in the wake of yet another instance of the administration raising student fees in order to fund construction of recreational facilities, the MSA has passed a resolution that, if put into effect, would require the administration to obtain the assent of students before raising student fees to fund non-academic construction.

Granted that students do have representation in university governance through bodies such as the Student Senate, on many important issues that directly affect them – from raising their fees to restructuring graduate education – they may be consulted, but are denied a voice in decisions. To shut students out of effective participation in decision-making is a travesty of the democratic principles the University purports to uphold. Certainly Minnesota could do as well as Wisconsin in this regard.

Monday, October 25, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Yes to a faculty member on the Board of Regents.

ReplyDeleteClearly shared governance is a joke. At least the students have a rep on the Board who can give direct input and be privy to deliberations.

I think that it is very important to hammer away on finances. At the last Board of Regents meeting, the president stated that the ACTUAL cost of education was $15K per student. This claim has also been made in justifying the outrageously low out of state tuition (not meaning reciprocity here).

So what is the basis for making these claims, Mr. President? And it seems that the state contribution, which is APPROXIMATELY the same as tuition should more than cover the deficit. So why, EXACTLY, does tuition need to be raised?

The other question is WHERE, exactly, does the money come from that pays for costs of research - approximately 30% according to VP Mulcahy - uncovered by granting agencies?

Getting the answer to these two questions about finances is essential if we are ever to make a case to the state legislature for more funding.

The administration continues to pound sand down a rat hole on this matter. A new study is being commissioned to demonstrate the economic benefit of the U to the state. OF COURSE there is one. But this study will do NOTHING to induce the lege to give us more money. Driven to Discover is also a hopeless waste of money as the Morrill Hall Gang fails to understand. Perhaps this is an ego trip? Certainly progress toward being one of the top three public research universities in the world is becoming an increasing joke when Madison - and many other US public universities - are clearly cleaning our clock. For yet more evidence, please see: http://bit.ly/946N7c

Answering the question about how much education and research actually costs and being honest about the answers is the way to go. Keep tuition down and educational quality up - that is our first priority. THEN put money - with the help of the state - toward research. Even REPUBLICANS will support research because aside from its intrinsic value - the reason why we do research - it is often good for business. And of course providing university trained undergraduates, professional students, and masters/doctoral level people is essential for the general welfare of the state.

Time for people in Morrill Hall to start being smart, rather than arrogant. Look what is happening to Tom Emmer. We are about to elect a governor who in the long run will help us. But we have to help him make a good case to the legislature and the citizens for more funding. The current Morrill Hall strategy has been a resounding disaster.

Where do we sign this document when you have final draft?

My best, Bill Gleason